Rage Against the Machine's Master Guitarist Deconstructs the Elements of His Style.

I'm often asked how I developed my approach to the guitar.� Well, I developed my unorthodox style of guitar playing in part by design and diligence, but also by chance and the occasional happy accident.� Through a combination of years of dedication to traditional practice routines and an irreverence for musical convention, I've come up with a sound which (on a good day) can both rock an arena and give you a nervous, unsettled feeling in the headphones.

When I was first learning to play, I loved the heavy guitar sounds of Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.� Those bands gave me a great appreciation for huge rock and guitar artistry.� Later, I was also a fan of punk, the Clash in particular.� The social awareness of their lyrical content showed me that a rock band could speak out about real issues within the context of powerful music.�� I could also see a direct correlation between the Clash and the rap band Public Enemy.� With both bands, the combination of lyrical brilliance with the radical nature of the music was something that fueled my interest in playing music and challenging conventions.� Since our inception, Rage Against the Machine have attempted to fuse the hugeness of metal riffs, the deep grooves of hip hop, a politically aware lyrical content and a punk ethos.� The cross-pollination of these styles is the cornerstone of all three of our albums.�

Long before Rage formed, though, I was inspired to learn scales and modes, and practice speed and technique for up to eight hours a day.� Neoclassical fret burners like Yngwie Malmsteen and fusion players like Al DiMeola were major inspirations.� As time wore on, though, I realized it was far more important for me to try to come up with something that reflected my own personality, as opposed to copying the approach of other players.�

Later, players like Allan Holdsworth, and Andy Gill of Gang of Four sparked my interest in pure "sonic" and "out" playing (playing unexpected or ear-bending notes).� Both of these players had created something truly unique in terms of sound.� I began to adopt a more irreverent attitude towards the instrument.� Armed with a Gibson Explorer, I stumbled upon the various uses of the toggle switch: by flicking the switch back and forth with one of the pickups completely off and the other all the way up, I discovered that I could create sounds and effects that I hadn't heard before coming out of a guitar.� Once that seed was planted, a twisted little sonic tree began to grow.�

When Rage first started to rehearse, I found myself playing alongside a genuine hip hop rhythm section, and my impression was that I had the choice to strum along in a "Chili Peppers" style and take the music in a funk direction, or attempt something altogether different.� I had just acquired the DigiTech Whammy Pedal, which I initially purchased because I intended to use it as a harmonizer.� But it also has a feature that causes the guitar's pitch to sound two octaves higher than played.� By using the Whammy Pedal, our music suddenly could sound like a Dr. Dre record.� By combining the Whammy effect with my toggle switching, I had all of the DJ sonic possibilities I needed (and more) within a simple guitar setup.� I wanted to see how far I could take this concept.�

At the time I was doing this, there was a prevailing attitude that the guitar was going to be made obsolete, either by keyboards or samples, or by some other innovation.� This notion seems to come down the pike every few years, like clockwork.� The sounds I was getting made me think that there was a possibility I'd be able to "turn the tables," as it were, and make DJs obsolete.�

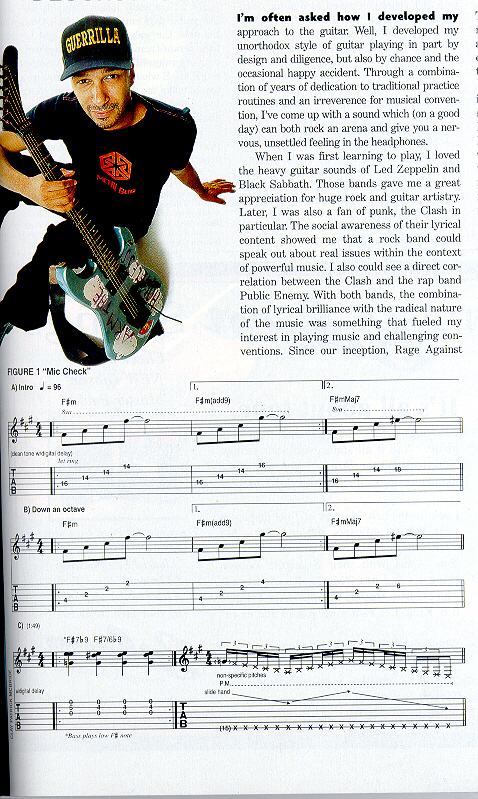

"Mic Check," from our latest album The Battle of Los Angeles, is a good example of a song on which I use a wide variety of guitar approaches.� For the bubbly, super-clean rhythm part in the intro, I used a Line 6 amp that I had in the studio.� The Line 6 is a "Twin" style amplifies in the studio that's a 2x12 combo; but it's also a programmable modeling amp that can fairly accurately approximate the sounds of many amps and effects, all of which are built into the amplifier.� I used the amp for a generic, clean tone and treated the signal with some Boss digital delay.

The "Mic Check" intro riff is comprised of a series of arpeggios based around an F# minor.� An arpeggio is sounded when the notes of a chord are played individually and in succession.�� As illustrated in the bar of Figure 1A, the very first thing I play is an ascending F# minor arpeggio in the 14th position.� I use my ring finger to fret the F# note on the D string at the 16th fret, and my index finger barres across the G, B, and high E strings at the 14th fret to sound the other three notes.� Each of these notes is picked only onve; the digital delay creates the impression that the notes are continually picked alternately through the entire bar.�

In bar two, I play the second arpeggio, which substitutes a G# on the high E string, 16th fret, for the high F#, and which is fretted with the pinkie.� Adding G# to the F# minor arpeggio yields an F# minor9 arpeggio.� After the F# minor arpeggio in bar 1 is repeated, the phrase ends in bar 3 with an unusual F# minor/major7 arpeggio, as the major seventh, E# (or F natural) is played in place of the high F#.� To play this high E#, I reach up with my pinkie, fretting the note on the B string.�

To start, try to play this part an octave lower, as it is shown in Figure 1B.� When you've become familiar with the riff, try moving it to other parts of the neck, and experiment by playing these three different arpeggios in a different order.�

At 1:49, the song shifts into another section, and at this point there are two distinctly different guitar parts.� One of the guitar parts consists of a progression of three-note chord voicings, with each chord plucked on each of the downbeats ("one," "two," "three," and "four").� With the delay pedal still set as it was during the verse section, I pluck all three strings at once in a "finger picking" style.� The middle finger of the left hand frets the E note on the B string, 5th fret, which is played in conjunction with the open G and high E strings (see Figure 1C).�

The other guitar part supplies the wild dugada-dugada-do sound.� This is played with the delay pedal set exactly as before, and with the picking hand palm-muting at the bridge.� I slide the middle finger of my fretting hand down and then up the low E string while picking 16th note triplets, sounding no particular pitches whatsoever.� Generally, I begin around the 15th fret of the low E string.� A similar riff is shown in Figure 1D.�

At 2:09, a new guitar part enters which sounds like a "laughing" guitar. To create this effect, the guitar is set so the bridge pickup is turned up full and the neck pickup is turned off.� I hold a metal slide with my left hand and hit across all of the strings with the slide right over the pickups while flicking the toggle switch back and forth, from "on" to "off," with my right hand.� The pitches are either higher or lower, depending on where along the string the slide lands.� Occasionally, the slide lands on the strings and is moved up and down with the toggle switch in the "on" position, thus bending the pitch of the noise.� A similar effect is heard in the solo section of the song "Fistful of Steel."�

At 2:19, a really insane-sounding and DJ-like guitar part enters: the slide is thrown to the side, the wah is turned on, and my left hand scrapes across all of the strings while I'm toggling away with the right hand.� Some occasional low E whammy bar dives are thrown in too, to make the damn thing "moo" like a cow.� I used this same technique (minus the cow) on "Bulls on Parade."

Hopefully this column will inspire you to pursue some of your own electric guitar madness.� See you next month.�